by Austin Lord

Sustained attention, even when it pains. This seems to be the guiding principle of photographer Kevin Bubriski, whose exhibition ‘Portraits of Nepal’ currently stands in Patan Durbar Square. First arriving in Nepal in the 1970s as a Peace Corps Volunteer, Bubriski, an intentioned and patient man, has since spent over nine years of his life in Nepal. His photographs are defined by the patience between them, one can read the pattern of his slow wending across the landscapes of Nepal. His images are filled with empathy, constructing a proximity that can be both enlightening and uncomfortable. He “seeks the stories behind faces” and shares what he finds, presenting both the joy and dukkha of Nepali lives with a kind of equanimity that fosters awareness and attention. Above all, Kevin is loyal to the integrity of his subject and the richness of their story; he listens well. Perhaps, this is why his photographs are both archetypal and resonant.

On Thursday morning, Kevin met with a group of people from the Langtang Valley, a place that he photographed while constructing drinking water projects there in 1976, a place that was devastated by the recent earthquakes and an avalanche that took the lives of an estimated 308 people. The Langtangpa assembled are participating in a photography workshop that will help them tell their own stories of dukkha, and Kevin leapt at the opportunity to meet with them. One of the young men in this group is the son of a man named Dorje who Kevin stayed with in Kyangjin Gompa decades ago, who asks Kevin to verify the stories he heard about Kevin’s fashionable blue Converse sneakers stitched together with dental floss [all true]. The years flow by.

Kevin points to a photograph of Gosainkunda, a sacred lake perched above and just outside the Langtang Valley and tells them why the water is so calm at that time of day. He points to a photograph taken in the village of Yarsa located on the old trail to Langtang and tells them: “I was standing here for almost an hour watching the two people work in the field, smoking a cigarette. It was only after a third person joined them that the image was just right. Do you see?” These stories are telling of his photographic practice and his use of the large-format camera, but they also speak to the embodied quality of his work. The steps, the paths, the miles between images.

The work exhibited here at BhaiDega in Patan Durbar Square was all produced between 1984 and 1987, during a period when Bubriski was shooting with a large format range-finder camera and was engaged in several long-term photographic projects. His work from the Kathmandu Valley is masterful, indicating the slow changes flowing through the city alongside the cultural paleochannels.

“Kathmandu seemed more finite then, more knowable.” The old man bowing to a shivalinga, the chaityas of Patan, the interior of a courtyard temporarily exposed to the world as the space changes around it, and a now famous portrait of two young Newar men in matching Michael Jackson sweatshirts. Despite Kevin’s tendency to spend months living in remote areas of Nepal, he has produced several excellent portfolios that speak to the deep tensions between heritage and change that shape the city. The urban images in the current exhibition are interspersed with work from the far corners of Nepal, at times highlighting the changing dimensions of the urban-rural divide, but also placing rural subjects on equal ground.

During this period, the first images that he made outside of the Kathmandu Valley were in the village of Barpak in Gorkha, the epicenter of the April 25 earthquake—a space that has been irrevocably and fundamentally changed, the origin of many post-earthquake images in recent months. Here, a photograph of two Gurung schoolboys from Barpak hangs next to another of a Tamang family standing in the doorway of their homes in Rasuwa. These are two areas and two ethnic groups that have been severely affected by the recent earthquakes, their dukkha has changed. Further along the wall, we see photographs from the Karnali region and Far-Western Nepal: the rooftops of Humla, a shaman and his son, masked dancers in full costume during a local ritual. A simple yet remarkable portrait of a young woman from Mugu looking straight into the camera, wearing a Dalai Lama locket but offering few markers to place her in time.

Bubriski’s photographs are seductive, unapologetically beautiful maybe. Many people report feeling a longing for something that is gone, or a nostalgia for a Nepal that is slipping away. Critiques of Bubriski’s work might focus on these qualities, arguing that his work plays too closely with depictions of Nepal now considered cliché and with a genre of work imbued with a Western or Orientalizing gaze. In most cases, however, the quality and temporal depth of Bubriski’s long-term engagement with Nepal seems to evade this framing—I would add that the direction of his more recent work further problematizes such characterizations. His images are timeless but they are not static; clear but not easy. Despite changes in his work and practice over the decades, the respect that he gives the subject does not. Tastes change, the mark of quality and intention does not.

Further, Bubriski’s work is subtly political, and not just aesthetic. His work shows poverty and hunger and hardship; he depicts the essential dignity of all kinds of people, without glamorizing these qualities. He treats everyone with the same formality, irrespective of class and position, which is itself a political decision. Arguably, just going to Humla in the 1970s was a political choice: living there for six months at a time and building drinking water systems as a Peace Corps volunteer is another story. The epochal changes of Nepal’s recent history are woven into his images in subtle ways: what is a Dalai Lama locket in 1985 as compared to a Dalai Lama locket today? How do we reinterpret the cultural themes of a Tharu wedding now in light of recent identity politics? Speaking to a packed house during his Artist’s Talk on Friday, Kevin uses his own images to point to a simple parallel: waiting. People in Humla were waiting for the king in 1976, waiting for government rice in the 1980s, and waiting for the helicopters of the World Food Programme in 2010. Kevin highlights the fact that despite a massive increase in development interest in Humla and a spike in the number of NGOs in Simikot, a village just a few hours walk away still seems remote. Flashing forward to a very recent image of young drug addicts on the streets of Kathmandu, Kevin simply states that “sometimes we have to be reminded of what we walk by.” This is all political commentary.

Most recently, Kevin came back to Nepal in the wake of the 2015 earthquakes, he created powerful images from (quite literally) the moment he stepped off the plane and he shared them via social media using tools like #NepalPhotoProject. He carries a digital SLR and an iPhone, using both tools interchangeably, maintaining a distinct style as he shares his work in new ways. Being aware of Kevin’s older work, I followed Kevin during this period as he delivered compelling images and stories day after day: narratives from IDP camps, a series showing the lives of informal laborers demolishing buildings, photographs from hard-hit areas of Sindhupalchowk and Bhaktapur, photos of the emptiness at Kasthamandap. Upon return, Kevin published a series of images taken using the Hipstamatic app on his iPhone, in the New York Times no less. He says that he is very compelled by this new “democracy of how we make images” but he misses the months he used to spend in the darkroom upon returning from fieldwork in Nepal. “I don’t know how I will be taking pictures next.” This curiosity seems to sustain him. Though Kevin’s early work may be of another generation, his photographic practice continues to evolve and he is actively contributing to the broader field of photography in Nepal.

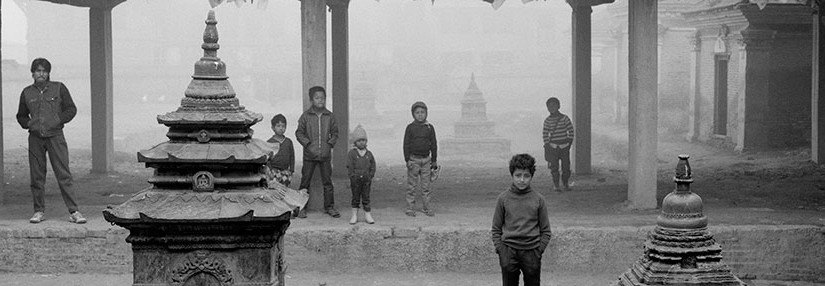

And for perhaps the same reasons, he can’t conceal the excitement of seeing hundreds of people engage with his work here in Patan. The first image in the show is a photograph of Patan Durbar square being swept in the early morning fog, an image that is no longer timeless because the temple, the column, and the statue of the Malla King silhouetted in the rear-ground have fallen. Seeing this image hung just steps away from these sites is meaningful to Kevin, because it means “bringing the work right back to where the images were made.” Some of the elders looking at the image reminisce about the winter mist that used to blanket Kathmandu in winters past; rarer now in the context of urbanization and climactic warming.

Since the installation process began, waves of people from all backgrounds and generations have engaged with these images. People shyly or brazenly walking up to the photographs, slowing down, spending minutes examining the details, walking away, walking back, touching the glass, taking their own photographs with them [in fact Kevin took his own selfie with his show], and calling family members on the phone to tell someone about what they are seeing. An old man with his cane; groups of teenage boys; women walking through the square carrying goods; my wife’s grandmother loves the exhibition. Across Patan, the patterns of public interaction during this festival are amazing. And in a way the temporal and spatial breadth of Kevin’s exhibition and his larger work places him in the center of this recent exhibition, as his work is both widely accessible and highly democratic.

This first Kathmandu Photo Festival, or #PhotoKTM, is an amazing public work. Rare in its commitment to truly engage the public and to make photography accessible and interesting to all kinds of audiences, and at a time when the city needs spark and hope. #PhotoKTM is leading the way, in a global sense. It is something new under the sun.

Kevin Bubriski, who has seen Nepal change so much over the years, knows this. And that is why, like others, he stands here in the center of a city that has yet to recover from the earthquake, surrounded by piles of bricks and temples that have collapsed, and he smiles.“This is so amazing, and I feel so honored to be here. I could never imagine this.” Sustained attention, even when it pains.

— Kevin is currently working on a project that builds on his photographic work from Syria in 2003. He lives in the United States and teaches at Green Mountain College in Vermont. His recent work will also be featured at Dartmouth College during the Nepal Earthquake Summit in February, and he is currently applying for a grant to return to Nepal in the coming year, so that he can continue to revisit the places he has photographed in the past decades.